Mysterious element promethium finally reveals its chemical properties

The highly unstable radioactive element promethium is hard to study in the lab, but chemists have now coaxed it into forming a compound in water so they can observe its bonding behaviour

By Alex Wilkins

22 May 2024

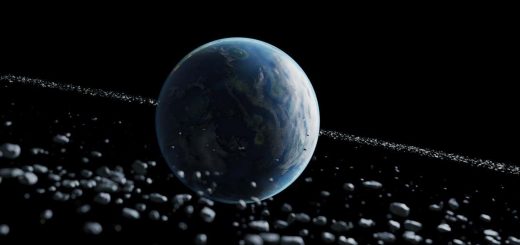

Conceptual art showing a compound of promethium

Jacquelyn DeMink, art; Thomas Dyke/photography; ORNL, UA.S. Dept. of Energy

A new compound containing one of the rarest elements in the world, promethium, has revealed its mysterious properties for the first time.

Promethium only exists naturally in minuscule amounts – Earth’s crust contains just about half a kilogram of the element. In 1945, researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee managed to produce it as a byproduct of the Manhattan Project’s plutonium enrichment programme. Its nuclear origins led to its name, after the Greek titan Prometheus, who stole fire and brought it to humans.

It is now routinely produced, albeit in tiny quantities, from the radioactive decay of uranium and can be incorporated in simple compounds for uses like luminous paint or nuclear batteries. But its extremely radioactive nature means it is inherently unstable, making it difficult to form long-lasting compounds that are easy to study. The crystal structures that it does exist in also exert forces on promethium’s chemical bonds, obscuring its fundamental chemistry, such as how long its atomic bonds are and how they form with other compounds.

Advertisement

Now, Alexander Ivanov at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and his colleagues have found a way to form a promethium compound in water. This dampens some of the damaging effects of radioactivity and avoids the obscuring effects of crystal structures, allowing the team to study the element’s chemistry in detail for the first time.

First, they synthesised a compound called bispyrrolidine diglycolamide (PyDGA), which is based on molecules that form compounds with elements similar to promethium. When promethium was added to this molecule in a solution, it formed the compound Pm-PyDGA, which has a bright pink colour due to its electron structure.

Fusion reactors could create ingredients for a nuclear weapon in weeks

Concern over the risks of enabling nuclear weapons development is usually focused on nuclear fission reactors, but the potential harm from more advanced fusion reactors has been underappreciated